Linux Inside a PDF

Want to learn ethical hacking? I built a complete course. Have a look!

Learn penetration testing, web exploitation, network security, and the hacker mindset:

→ Master ethical hacking hands-on

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life!

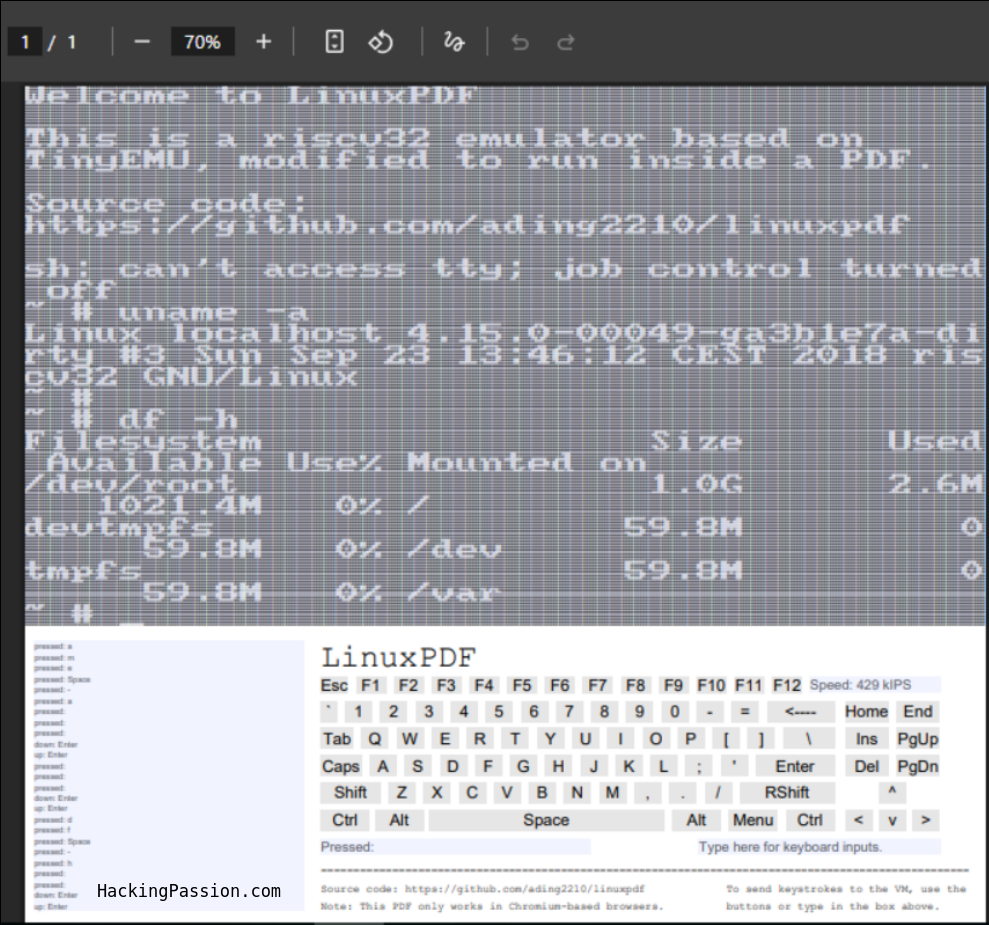

Linux running inside a PDF. An actual working operating system with a terminal where you can type commands. Open a PDF in Chrome. Wait 30 seconds. You now have a working Linux terminal. No installation, no software, just a 6MB file that boots an entire operating system.

A high school student named Allen built this, the same kid who previously crammed Doom into a PDF. Before that he made tools to bypass school software restrictions and exploits to boot Linux on locked-down Chromebooks.

I love this kind of stuff because someone sees a limitation and thinks: what if I just ignore that? What if I push it further? That mindset is exactly what hacking is about.

PDFs can run JavaScript, and not just simple form validation but full computational logic. The specification allows 3D rendering, HTTP requests, and even detection of how many monitors are connected to a system. Adobe built an entire programming environment into what most people think is just a document format.

Think about that for a second. The invoice your accountant sends you, the resume someone emails, the boarding pass you download… all of them could theoretically run code.

Allen took a RISC-V emulator called TinyEMU that was originally created by Fabrice Bellard. If that name sounds familiar, Bellard also created QEMU and FFmpeg, and back in 2011 he built the first JavaScript-based PC emulator that could run Linux in a browser. The guy once held the world record for calculating pi to 2.7 trillion digits, so Allen is building on the shoulders of a legend here.

The trick was getting the emulator to run inside Chrome’s limited PDF JavaScript engine. Modern browsers use WebAssembly for heavy computation but PDF engines do not support it, so Allen found an old version of Emscripten from 2019 that compiles C code to asm.js instead. That older format works inside the PDF sandbox.

The display renders as ASCII characters where each line of the terminal output sits in a separate text field, and keyboard input comes through a virtual keyboard made of PDF buttons or by typing into a text box.

- → Boot time: 30 to 60 seconds

- → File size: 6MB

- → Performance: roughly 100 times slower than normal Linux

- → Works in: Chrome, Edge, Brave, and other Chromium browsers

- → Does not work in: Adobe Reader, Firefox

I tested it on my Linux system first and the emulator ran fine, but the terminal display did not render correctly. Chrome on Linux has issues with the text field rendering in PDFs, so the emulator was working but I could not see the output. After trying Chromium, a Firefox fork, and adjusting Chrome flags I finally got it running properly on a different system where it booted, showed the kernel messages, and let me run commands like uname -a, ls, whoami, free -m and df -h.

Seeing a working Linux shell inside a PDF is something else, a full operating system running inside a document format with all the possibilities that brings.

Why is it so slow? Chrome intentionally disables the JIT compiler when running JavaScript inside PDFs as a security measure. JIT compilation creates executable code at runtime which attackers could potentially abuse, so by forcing the engine to interpret code instead of compiling it Chrome trades performance for safety.

The irony here is thick because a security feature meant to protect users is exactly what makes this possible. Without JIT disabled, running an entire operating system inside a PDF would be an obvious attack vector, but with JIT disabled it becomes a harmless yet impressive demonstration.

And that brings up the real question: if someone can run Linux in a PDF, what else can run in a PDF?

Security researchers have been warning about PDF JavaScript for years. In May 2024 CVE-2024-4367 exposed arbitrary JavaScript execution in PDF.js, the engine Firefox uses for PDFs. The vulnerability allowed attackers to execute code just by getting someone to open a malicious file, and in Electron apps without proper sandboxing this led to full native code execution on the target machine.

Check Point Research published data showing 22% of all email-based cyberattacks now use PDF files as the delivery mechanism, which means the format that everyone trusts as safe has become one of the most common attack vectors.

Allen does not seem worried though. In an interview with The Register he said embedding JavaScript in PDFs is nothing new and that modern PDF engines were built with these risks in mind. He thinks opening a PDF in Chrome is probably safer than visiting a random webpage. He has a point because the sandbox is real, the JIT is disabled, and the attack surface is limited compared to a full browser tab. But the gap between what PDFs can theoretically do and what most people assume they can do remains massive.

Thomas Rinsma, a security analyst, started this whole trend on January 5, 2025 when he released PDFTris, a playable Tetris game inside a PDF. Nine days later Allen had Doom running, and a month after that a full Linux system.

The progression tells a story about how hackers think: see a constraint, find a workaround, push the boundary, see what breaks. Each project builds on the last and each one reveals a little more about what the format can actually do. PDFTris was a toy, DoomPDF was a flex, and LinuxPDF is proof that documents are not just data.

For defenders the takeaway is simple: PDFs are executable formats and they have been for decades. The JavaScript specification, 3D rendering capabilities, and network access built into the format mean that a PDF is closer to a webpage than a piece of paper, and most security training still treats PDFs as safe documents which needs to change.

Understanding how file formats actually work is a core part of security research. I cover reconnaissance, system internals, and attack surfaces in my ethical hacking course:

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life.

Try LinuxPDF yourself (Chromium browsers only):

GitHub:

→ Stay updated!

Get the latest posts in your inbox every week. Ethical hacking, security news, tutorials, and everything that catches my attention. If that sounds useful, drop your email below.