Why It Took Microsoft 32 Years to Disable NTLM

Want to learn ethical hacking? I built a complete course. Have a look!

Learn penetration testing, web exploitation, network security, and the hacker mindset:

→ Master ethical hacking hands-on

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life!

32 years. That is how long it took Microsoft to disable NTLM, the protocol that handles Windows login authentication. A broken system linked to $10 billion in damages and some of the worst cyberattacks ever recorded. Hackers have been exploiting it since 2001. Here is the story of why it took this long.

On January 30, 2026, Microsoft announced they will finally disable NTLM by default in future Windows releases.

NTLM was introduced in 1993 with Windows NT. It handles authentication using a challenge-response mechanism: the server sends a random challenge, the client responds with a hash derived from the password, and if the hash matches, access is granted. Simple enough. The problem is that NTLM never verifies who it is actually talking to.

In 2001, a security researcher published a tool called SMBRelay that demonstrated something alarming. An attacker sitting between a client and server could intercept the authentication and relay it to a different target. The server would happily accept it because NTLM has no way to verify that the response came from the same connection that requested it.

Microsoft knew about this. They patched the specific attack vector in 2008, seven years later, but the underlying protocol weakness remained untouched.

Then came Mimikatz.

In 2011, a French security researcher named Benjamin Delpy discovered something disturbing about how Windows handles credentials. The operating system stores encrypted passwords in memory, which sounds reasonable, but it also stores the decryption keys in the same location. Delpy built a tool to demonstrate this and reported it to Microsoft.

Their response was essentially that the attacker would already need access to the machine, so it was not a real problem.

Delpy saw something Microsoft missed. One compromised machine means access to credentials that unlock other machines. Those credentials unlock more machines. A single foothold becomes total network compromise.

In 2012, Delpy attended a security conference in Moscow. When he returned to his hotel room, he found a stranger sitting at his laptop. The man demanded a USB stick with the Mimikatz source code. Delpy was shaken. He decided that if attackers were going to get their hands on it anyway, then defenders should have it too. He released Mimikatz as open source on GitHub.

The tool spread fast. Within months it appeared in a major attack against a Dutch certificate authority that resulted in 300,000 people having their communications intercepted. The company went bankrupt. Between 2013 and 2018, criminal operations using similar techniques stole over $1 billion from banks across 30 countries. In 2015, attackers breached the German parliament and compromised thousands of emails including those of senior officials.

The worst was yet to come.

In June 2017, malware called NotPetya spread across the world in hours. It combined a leaked NSA exploit with credential-stealing techniques that grabbed NTLM hashes from memory. Once it landed on a single machine, it dumped credentials and used them to spread to every other system on the network.

The damage was staggering. A major shipping company had 17 of its 76 port terminals go offline and had to replace 45,000 computers and 4,000 servers. The only reason they recovered at all was a stroke of luck: one domain controller in Ghana had been offline during the attack due to a power outage, giving them a single clean backup to rebuild from. A pharmaceutical company lost $870 million. A delivery company lost $400 million through one subsidiary alone. Total estimated damage exceeded $10 billion.

NotPetya was not ransomware in any real sense. The payment mechanism was fake. There was no working decryption key. It was built to destroy, and NTLM credential theft was central to how it spread so fast.

The attacks kept evolving. In 2021, security researcher Gilles Lionel published PetitPotam, a technique that forces Windows servers to authenticate to an attacker-controlled destination. Combined with relay attacks, an unauthenticated attacker could potentially take over an entire domain. Security researchers tested it and the assessment was blunt: this attack is too easy.

New variations keep appearing. In 2024 and 2025, multiple vulnerabilities were discovered that allow NTLM hash theft with minimal user interaction. Some required nothing more than viewing a folder containing a malicious file. Attackers do not need sophisticated exploits when the protocol itself is broken at a fundamental level.

So why did this take 32 years to disable?

Backwards compatibility. NTLM is everywhere. Legacy applications depend on it. Systems that cannot run Kerberos fall back to it. Workgroups and local accounts use it. Disabling NTLM would break things, and breaking things in enterprise environments is politically difficult.

Microsoft introduced Kerberos as the preferred protocol back in 2000, but NTLM remained enabled as a fallback. For over two decades, that fallback has been exploited over and over again.

Here is what is changing now.

Microsoft announced a three-phase plan. Phase one provides auditing tools in Windows 11 24H2 and Windows Server 2025 so administrators can see exactly where NTLM is still being used. Phase two, scheduled for the second half of 2026, introduces features to handle scenarios that currently force NTLM fallback. Phase three disables network NTLM by default in future releases.

Important detail: NTLM is not being removed entirely. It will still exist and can be re-enabled through policy controls. This is about changing the default from enabled to disabled.

NTLMv1 has already been removed from Windows 11 24H2 and Windows Server 2025. Starting in October 2026, NTLMv1-derived credentials will be blocked by default.

Here is what makes NTLM so dangerous technically.

NTLM relay attacks work because the protocol lacks mutual authentication. The client proves its identity to the server, but the server never proves anything back. An attacker in the middle can forward those authentication messages to a different target and gain access with the victim’s privileges.

Pass-the-hash attacks exploit the fact that NTLM uses the password hash directly for authentication. If an attacker obtains the hash, they do not need to crack it. They can use it as-is to authenticate anywhere that accepts NTLM. The hash becomes the password.

The mitigations that exist, things like SMB signing, LDAP signing, and Extended Protection for Authentication, all add verification that ties authentication to a specific connection. But most of these are not enabled by default, and many organizations never turn them on.

Kerberos avoids these problems through mutual authentication, ticket-based access, and cryptographic binding to specific sessions. It is not perfect, but it does not have the fundamental architectural flaws that make NTLM dangerous.

The tools attackers use for this are not secret. Responder poisons LLMNR and NBT-NS requests to capture NTLM hashes on the local network. Mimikatz dumps credentials straight from memory using commands like sekurlsa::logonpasswords to extract plaintext passwords and NTLM hashes from the LSASS process. NTLMRelayX from the Impacket toolkit takes captured authentication and forwards it to other targets. PetitPotam and PrinterBug force servers to authenticate to attacker-controlled destinations. All of these are freely available and well documented.

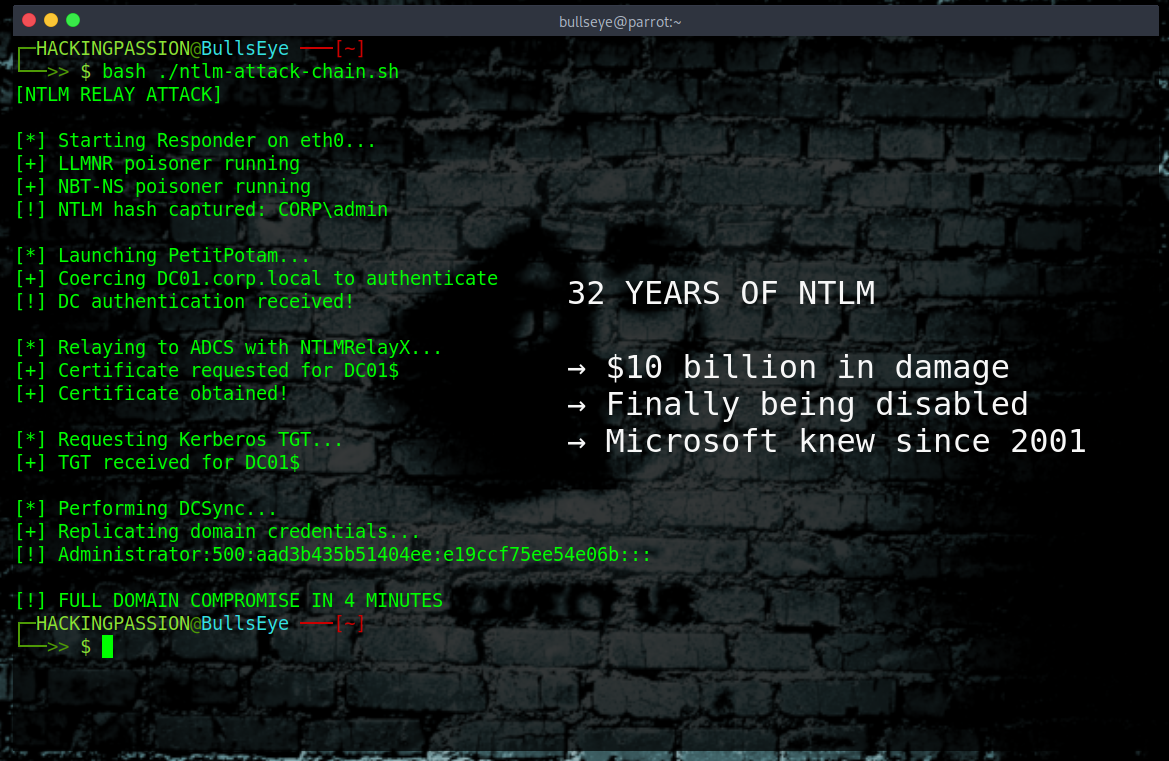

Here is what a full attack chain looks like in practice:

→ Attacker gets initial foothold on the network through phishing or compromised credentials

→ Runs Responder to poison name resolution and capture NTLM hashes from systems trying to authenticate

→ Uses PetitPotam to coerce a domain controller into authenticating to the attacker’s machine

→ Relays that authentication to Active Directory Certificate Services using NTLMRelayX

→ Requests a certificate for the domain controller account

→ Uses that certificate to request a Kerberos ticket

→ Performs a DCSync attack to dump all password hashes from the domain

→ Game over. Full domain compromise from a single foothold.

This entire chain can execute in minutes once the attacker has network access. No zero-days required. No advanced exploits. Just a broken protocol that has been broken for decades.

What to do right now:

→ Audit NTLM usage using the new logging in Windows Server 2025 and Windows 11 24H2 → Enable SMB signing on all systems, not just domain controllers → Enable LDAP signing and channel binding on domain controllers → Enable Extended Protection for Authentication where supported → Consider enabling Credential Guard on Windows 10 and later to protect credentials in memory → Identify applications that hardcode NTLM instead of using the Negotiate package → Plan for the transition before Microsoft forces the change

The auditing events are logged to Applications and Services Logs → Microsoft → Windows → NTLM → Operational. Client systems log Event ID 4020 and 4021 when attempting NTLM authentication, servers record Event ID 4022 and 4023. Each entry shows which process triggered the authentication and why NTLM was used instead of Kerberos.

For anyone managing Windows networks, this change has been coming for years. The question was never if Microsoft would disable NTLM, but when they would finally commit to doing it.

Understanding how attackers intercept credentials, move through networks, and exploit system weaknesses is fundamental to security. I cover network attacks, traffic interception, and hands-on exploitation techniques in my ethical hacking course:

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life.

→ Stay updated!

Get the latest posts in your inbox every week. Ethical hacking, security news, tutorials, and everything that catches my attention. If that sounds useful, drop your email below.