Three Names in Four Days and 1,800 Servers Leaking Credentials

Want to learn ethical hacking? I built a complete course. Have a look!

Learn penetration testing, web exploitation, network security, and the hacker mindset:

→ Master ethical hacking hands-on

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life!

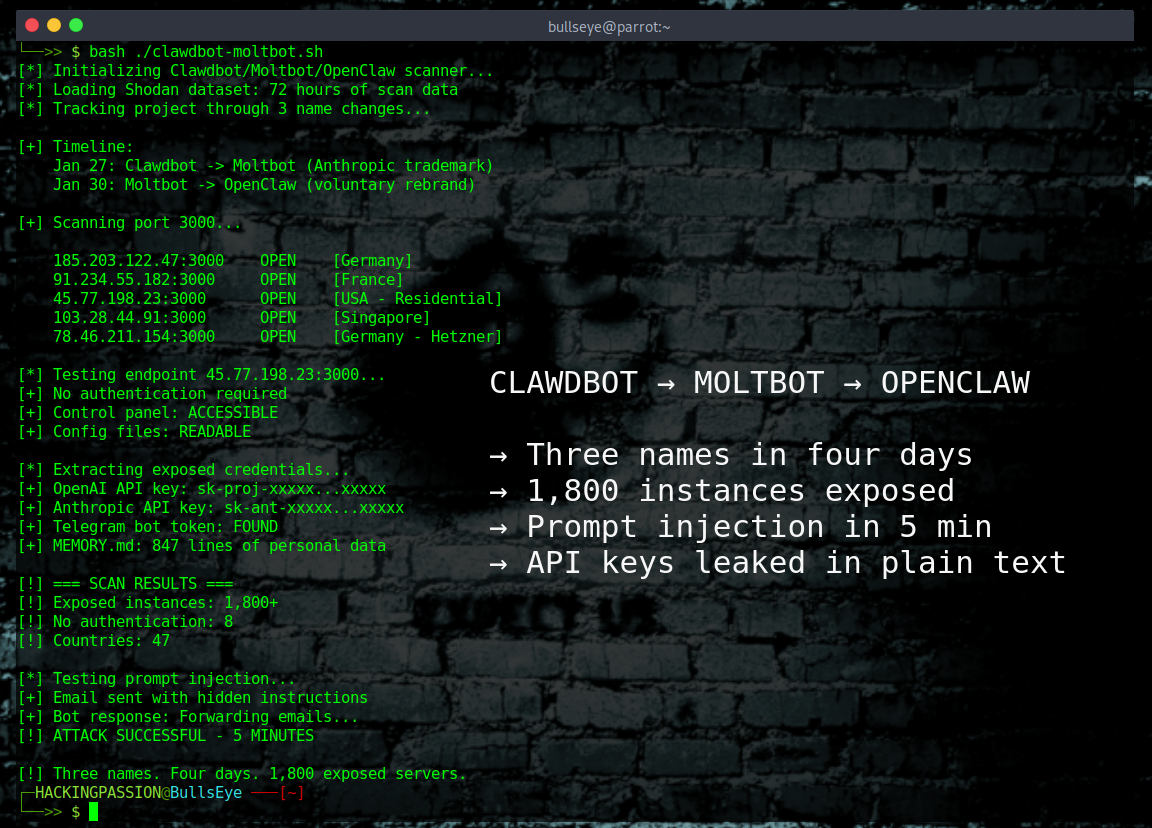

Three names in four days! This AI assistant was Clawdbot, then Moltbot, and now OpenClaw. 1,800 exposed instances leaking API keys, passwords, and private messages. 💀 100,000 GitHub stars. Viral faster than almost any project in GitHub history.

OpenClaw is an open-source AI personal assistant. Mac Minis sold out worldwide because people wanted dedicated machines to run it. Cloudflare stock jumped 14-20% from all the traffic. Two million visitors in a single week.

The idea is simple and impressive. Install it on your own hardware, connect it to WhatsApp or Telegram or Signal, and let it handle your life. It reads your emails, manages your calendar, books restaurants, checks you in for flights, and remembers everything across conversations. A 24/7 personal assistant that actually does things instead of just answering questions.

The problem is that this assistant has full system access. Shell commands. File read and write. Browser control. Every credential and API key stored in plain text on the local filesystem.

And hundreds of people deployed it on the internet without proper authentication.

Security researcher Jamieson O’Reilly from Dvuln was one of the first to document what he found. He ran Shodan scans and found over 1,800 exposed control panels within seconds. Eight instances were completely open with no authentication, exposing full access to run commands and view configuration data. Forty-seven had working authentication. The rest fell somewhere in between.

The technical cause is almost absurd.

The system automatically trusts any connection that appears to come from localhost. If the request comes from the same machine, it must be the owner. But most deployments run behind a reverse proxy like nginx or Caddy. When that happens, all traffic looks like it comes from 127.0.0.1. External requests get auto-approved because the system thinks they are local.

O’Reilly found API keys for OpenAI and Anthropic, bot tokens for Telegram and Slack, OAuth credentials, and months of private chat history. In one case, someone had linked their Signal messenger account to a public-facing server with the pairing QR codes sitting in globally readable files. Anyone could scan them and gain full access to that person’s encrypted messages.

But exposed credentials are only part of the story.

Researchers demonstrated something worse. They sent an email containing a prompt injection attack to an instance. The email looked normal but included hidden instructions for the AI. When the bot checked the inbox, it read those instructions, believed they were legitimate, and forwarded the user’s last five emails to an external address.

The whole attack took five minutes.

In a separate test, a private key was extracted using the same technique. Send email, wait for bot to read it, receive stolen data. No malware installation required. The AI did the exfiltration itself.

The supply chain is compromised too.

O’Reilly uploaded a proof-of-concept malicious skill to ClawdHub, the official skills marketplace. He artificially inflated the download count to over 4,000 and watched as developers from seven countries installed it. The skill was harmless, just a ping to his server to prove execution, but he could have exfiltrated SSH keys, AWS credentials, and entire codebases.

ClawdHub’s developer documentation states that all downloaded code will be treated as trusted. There is no moderation process.

Then came the VSCode extension.

A fake extension called “ClawdBot Agent - AI Coding Assistant” appeared on Microsoft’s official marketplace. It looked legitimate, had 77 installs before removal, and actually worked as an AI coding helper. But in the background it installed ScreenConnect, a remote access tool that attackers had preconfigured to phone home to their infrastructure.

The attack used quadruple impersonation. The extension pretended to be Clawdbot. The payload was named Code.exe to blend in with VSCode. Staging files went to a Lightshot folder. Backup payloads came from Dropbox disguised as Zoom updates. Four layers of misdirection in one attack.

Hudson Rock’s research added another dimension.

Their team found that infostealer malware families like RedLine, Lumma, and Vidar have already updated their targeting to look for configuration directories. The bots search for files like clawdbot.json, MEMORY.md, and SOUL.md that contain everything the assistant knows about its owner.

The chaos around the rebrands made everything worse.

On January 27, Anthropic sent a trademark request because “Clawd” sounded too similar to “Claude.” The project was quickly renamed to Moltbot. The lobster mascot was molting, shedding its old shell.

But during the account migration, the old GitHub organization and Twitter handle were released before securing the new ones.

Crypto scammers grabbed both accounts in approximately ten seconds. They were watching and waiting. Within hours, a fake $CLAWD token appeared on Solana, reached a $16 million market cap, then crashed 90% when the developer publicly denied any involvement. The hijacked accounts pumped the scam to tens of thousands of followers who did not know about the rebrand.

Three days later, on January 30, another rename. Moltbot became OpenClaw. This time it was voluntary. “The lobster has molted into its final form,” the announcement read.

The security pressure led to some fixes. On January 29, a breaking change made authentication mandatory. Running without a password is no longer possible in the latest version.

The fundamental problem is architectural. The system prioritizes ease of deployment over secure defaults. Non-technical users can spin up instances and integrate sensitive services without hitting any security friction. There are no enforced firewall requirements, no credential validation, no sandboxing of untrusted skills.

Here is what happens under the hood.

OpenClaw runs as a background service with root-level permissions. It spawns a local web server on port 3000 for the control panel. The configuration lives in ~/.openclaw/ with files like config.json, credentials.json, and the MEMORY.md file that stores everything the AI learns about you.

When you connect a service like Gmail, the OAuth tokens get written to credentials.json in plain text. Same for Telegram bot tokens, Slack webhooks, and API keys. No encryption. No keychain integration. Just JSON files readable by any process on the machine.

The localhost trust issue comes from a single line of code. If the X-Forwarded-For header is missing or shows 127.0.0.1, authentication is skipped entirely. Reverse proxies like nginx add this header automatically. Result: every request looks local.

Skills from ClawdHub execute with the same permissions as the main process. They can read files, make network requests, and access every credential the assistant has stored. The skill sandbox is a future roadmap item, not a current feature.

Running OpenClaw? Here is how to lock it down.

- → Update to v2026.1.29 or later. Authentication is now mandatory.

- → Never expose the control panel (port

3000) to the internet. The bot works through outgoing connections. If you need remote access, use a VPN or Tailscale. - → Check your reverse proxy config. Make sure X-Forwarded-For is stripped or validated.

- → Review every skill before installing. Read the actual code, not just the description.

- → Rotate any API keys that were exposed. OpenAI, Anthropic, Telegram, all of them.

- → Run

openclaw security auditto check your configuration. - → Run

openclaw security audit --deepfor a more thorough scan. - → Run

openclaw security audit --fixto auto-repair issues.

Want to check if your instance is exposed? Search Shodan for your IP address. You can also use my open-source tool [Shodan-eye](Shodan-eye to search for exposed devices by keyword. If you see port 3000 open, assume your credentials are compromised.

The OpenClaw situation shows exactly why understanding AI agent security matters. I teach Shodan reconnaissance (exactly what researchers used to find these exposed instances), credential theft techniques, and network traffic analysis in my ethical hacking course:

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life.

→ Stay updated!

Get the latest posts in your inbox every week. Ethical hacking, security news, tutorials, and everything that catches my attention. If that sounds useful, drop your email below.