Fake SymPy Package Deploys Fileless Cryptominer on Linux Systems

Want to learn ethical hacking? I built a complete course. Have a look!

Learn penetration testing, web exploitation, network security, and the hacker mindset:

→ Master ethical hacking hands-on

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life!

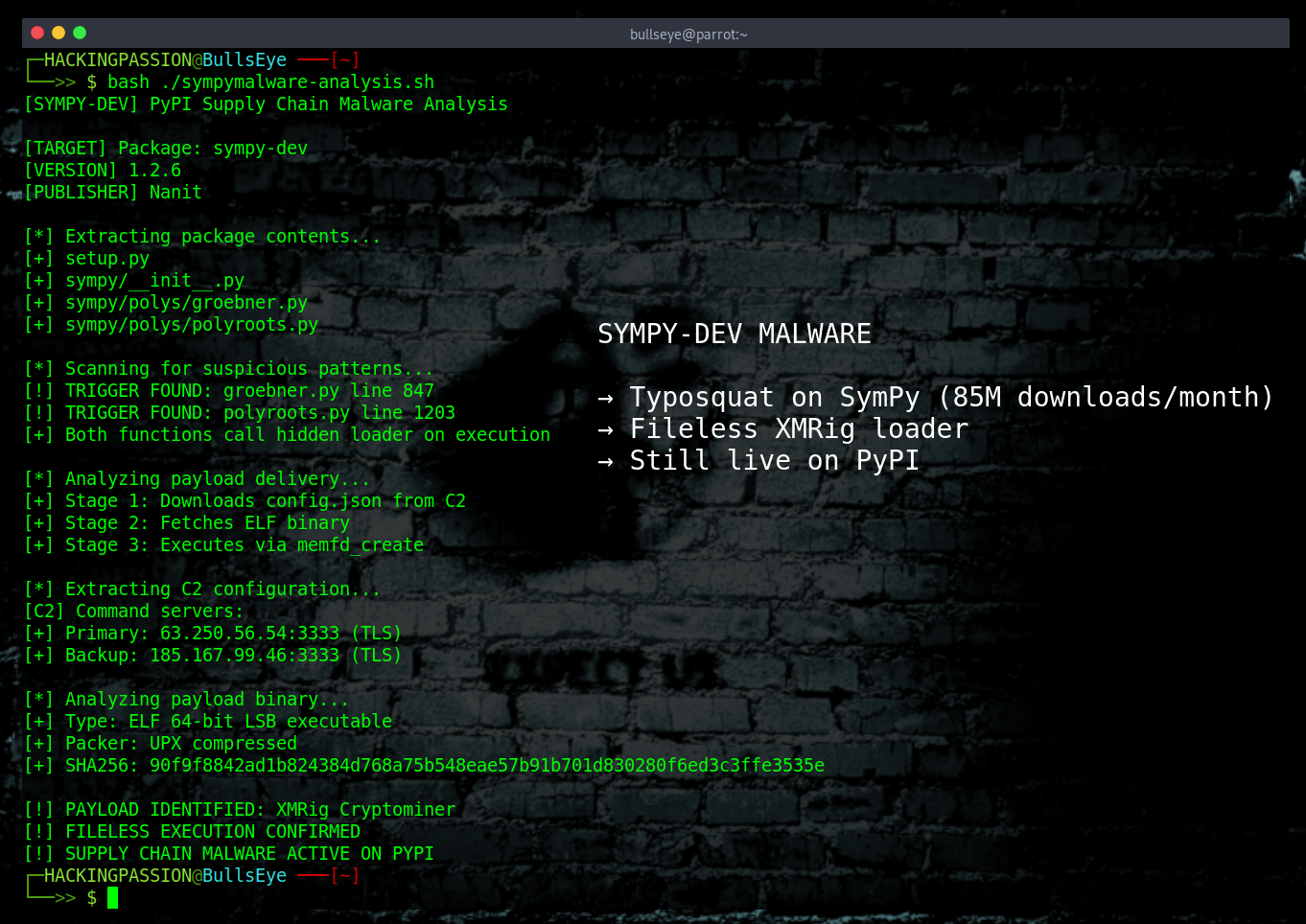

A fake SymPy package deploys XMRig cryptominers on Linux machines. The malware hides inside polynomial functions. It only activates when you do math. Over 1,000 downloads in day one. Still live on PyPI. The real SymPy has 85 million downloads per month. That is the target size. 🧐

Socket’s Threat Research Team found this on January 21, 2026. The attacker copied SymPy’s entire project description and branding, then uploaded it under a name that looks like a development build. Developers searching for SymPy or copy-pasting requirements might grab the wrong package without noticing.

The malware does not activate on import. It waits until specific polynomial functions run. Functions like groebner() for solving polynomial systems or roots_cubic() for cubic equations. If you have no idea what those mean: they are standard math operations that researchers and engineers use constantly. The backdoor hides inside the actual algebra.

Run one of these functions and the malware wakes up. It downloads a JSON config file from the attacker’s server. Then it fetches a Linux ELF binary, basically an executable program ready to run on Linux.

Here is where it gets interesting.

The payload never touches the disk as a normal file. The malware uses a Linux feature called memfd_create to create an anonymous file that exists only in memory. Think of it as writing on a whiteboard instead of paper. It writes the binary into this memory space, marks it executable, and runs it through /proc/self/fd. Security tools looking for suspicious files on disk see nothing. The payload runs, does its job, and leaves almost no trace. Reboot the system and the whiteboard is wiped clean.

In this campaign, the payload is XMRig. A cryptocurrency miner that burns CPU to mine Monero. The config enables CPU mining and disables GPU. Why? Because research servers and cloud instances often have powerful CPUs but basic graphics cards. The attacker knows exactly what hardware they are targeting. Two C2 servers at 63.250.56.54 and 185.167.99.46 deliver the payload over TLS on port 3333.

Version 1.2.6 added a second trigger function pointing to the second server. This is not laziness. This is operational security. If one server gets blocked or taken down, the other keeps working. The attacker built a backup plan into the malware itself.

But the miner is not the real concern. Pay attention here.

This thing is a loader. It can grab and run any code the attacker wants. Today it mines crypto. Tomorrow it could be ransomware, an infostealer, or a way deeper into the network. The loader stays. Only the payload changes. That is the danger most people miss when they hear “cryptominer” and think it is just about stolen CPU cycles.

The attacker published under the username Nanit on PyPI. Beyond that, attribution gets murky. In cybersecurity, attribution is one of the hardest problems. Usernames can be fake. Infrastructure can be rented. What we know for certain is how the malware works and that it remains accessible for download.

Why target SymPy users? The library runs everywhere: universities, research labs, engineering firms, machine learning pipelines, HPC clusters. Lots of CPU power, often not much security monitoring. Perfect for mining. And Linux dominates these workloads, which explains why the payload only targets Linux.

This attack fits a pattern. Over the past two years, multiple PyPI campaigns have used the same playbook: typosquat a scientific library, hide a cryptominer, use memfd_create for fileless execution. The secretslib package in 2025 did exactly this. So did PyLoose in 2023. Attackers are recycling what works. The technique is proven, the targets are predictable, and the defenses are still catching up.

Socket has requested removal from PyPI, but at the time of their publication the package remained live.

Indicators of Compromise:

- → Package:

sympy-dev(versions 1.2.3 through 1.2.6) - → Publisher: Nanit

- → C2 servers:

63.250.56.54and185.167.99.46 - → Mining endpoints: port 3333 over TLS on both servers

- → Payload hashes (SHA256):

90f9f8842ad1b824384d768a75b548eae57b91b701d830280f6ed3c3ffe3535ef454a070603cc9822c8c814a8da0f63572b7c9329c2d1339155519fb1885cd59

Protection:

- → Check what you have installed:

pip list | grep sympy - → The real package is

sympy, notsympy-dev - → Lock your dependencies and verify hashes before installing

- → Watch for Python processes making weird network connections

- → Block the C2 IPs at your firewall

Supply chain attacks keep evolving. Typosquatting works because developers trust familiar names. A single wrong character in a package name opens the door.

I cover how attackers hide malware and evade detection. Understanding how attackers think is the first step to stopping them. I teach ethical hacking from zero to expert:

Join my complete ethical hacking courseHacking is not a hobby but a way of life.

→ Stay updated!

Get the latest posts in your inbox every week. Ethical hacking, security news, tutorials, and everything that catches my attention. If that sounds useful, drop your email below.