52-Year-Old Unix Tape Reveals the Same Buffer Overflow We're Still Making Today

Want to learn ethical hacking? I built a complete course. Have a look!

Learn penetration testing, web exploitation, network security, and the hacker mindset:

→ Master ethical hacking hands-on

(The link supports me directly as your instructor!)

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life!

A 52-year-old tape just revealed a buffer overflow that looks exactly like the bugs we’re still finding today. 😏

In July 2025, someone found a magnetic tape from 1973 in a storage room at the University of Utah. Handwritten on the label: “UNIX Original From Bell Labs V4”. This turned out to be the only surviving copy of Unix v4, the 1973 version where Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie rewrote the entire operating system from assembly into C.

That rewrite changed everything about how operating systems worked. Before Unix v4, operating systems were locked to specific hardware, but after the C rewrite the same code could run on different machines. This is why Unix-like systems now power everything from iPhones to supercomputers.

In December 2025, researchers got the tape working in a PDP-11 simulator. And then they started looking at the source code.

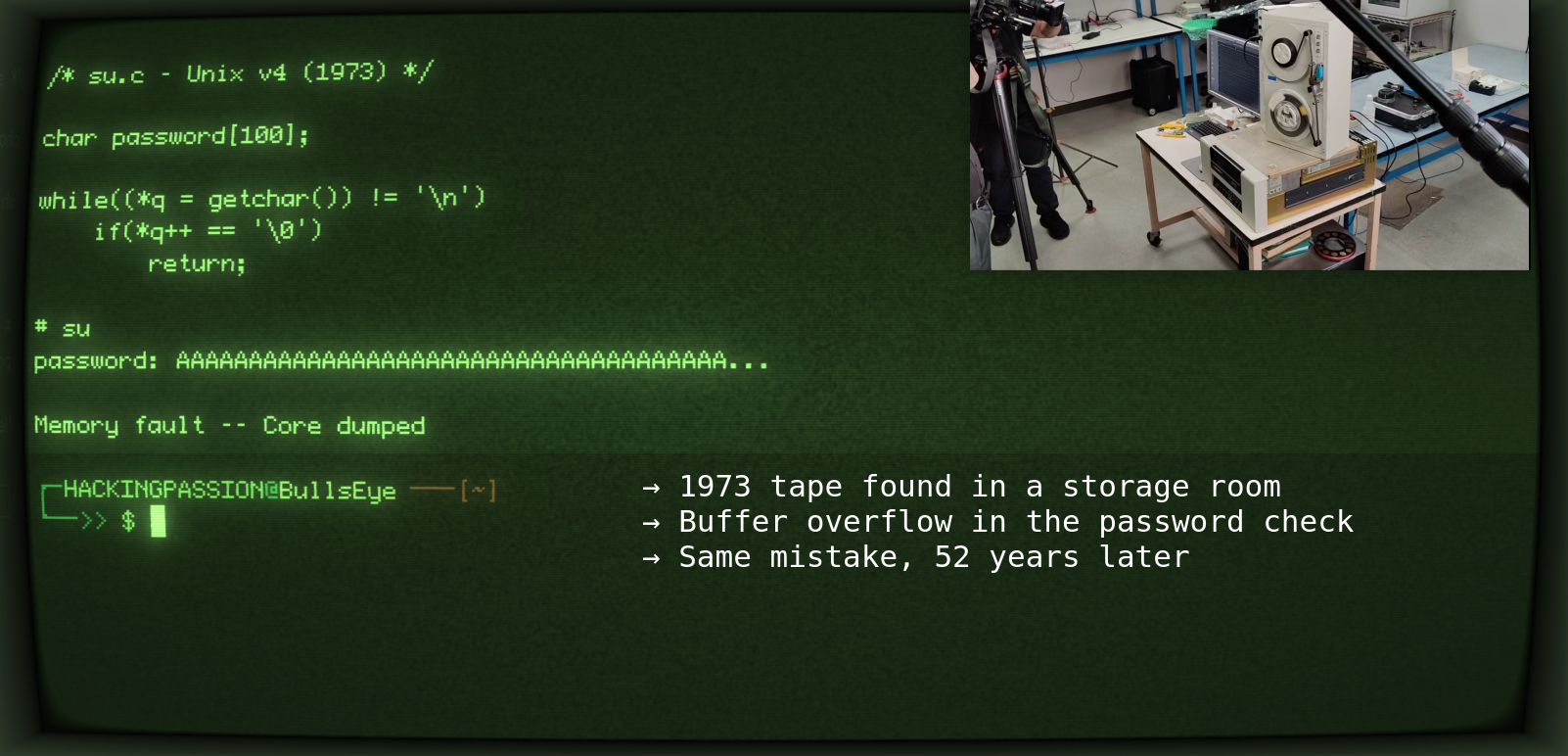

The buffer overflow in su.c

The su program makes you root. You type your password, the system checks the hash, and if it matches you get a root shell. The entire program is less than 50 lines.

Here’s the problem:

| |

The password buffer is 100 bytes. The loop reads characters until it hits a newline. But there’s no check whether you’ve already filled those 100 bytes.

Type more than 100 characters and you overwrite adjacent memory:

| |

This is a classic stack-based buffer overflow, the mother of all security bugs.

Doug McIlroy, who managed the Bell Labs team that built Unix, responded to this discovery: “Overflowable buffers were common in those days.”

In 1973, security wasn’t a concern. Computers sat in locked rooms with trusted users. The idea that someone might deliberately overflow a buffer to exploit a system wasn’t on anyone’s radar.

The first real buffer overflow exploit came 15 years later. The Morris Worm in 1988 used a buffer overflow in fingerd to infect about 6,000 computers, roughly 10% of the entire internet at that time.

And we’re still making the same mistakes. In January 2021, CVE-2021-3156 revealed a heap-based buffer overflow in sudo that had been sitting there for almost 10 years. In June 2025, CVE-2025-32463 hit sudo again with privilege escalation, CVSS 9.3, actively exploited in the wild.

Unix v4 came with complete source code and a C compiler. You could patch and rebuild the system on itself without external tools.

The fix adds a counter that tracks how many characters have been read:

| |

Compile, move to /bin/su, set the setuid bit, and you’re running a patched system.

The researcher who wrote this fix initially tried pointer arithmetic, which would be the normal way to do it in modern C, but the 1973 compiler accepted the syntax without generating working code so the simpler index-based check had to do.

Of course, Unix v4 had no networking so you couldn’t exploit this remotely, but the same class of bug in networked software has caused massive damage over the decades.

The pattern hasn’t changed

In the first 16 days of January 2025 alone, 134 new Linux kernel CVEs were published. Windows had its own parade of heap overflows throughout the year. Over 21,500 vulnerabilities were disclosed in just the first half of 2025, affecting everything from kernels to drivers to system services.

Buffer overflows exist because C lets you write past array boundaries without warning, and the fix is simple bounds checking, but programmers keep forgetting to add it.

→ 1973: No bounds check in su.c → 1988: Morris Worm exploits buffer overflow in fingerd → 1997: Similar syslog bug reported in Linux libc → 2001: Code Red uses buffer overflow in IIS, 359,000 Windows systems in 14 hours → 2021: sudo vulnerability sits undetected for a decade → 2023: “Looney Tunables” - buffer overflow in glibc’s dynamic loader, full root access → 2024: glibc syslog() heap overflow - same type of bug as 1997, same mistake in newer code → 2025: sudo hit again (CVE-2025-32463), critical privilege escalation, CISA KEV → 2025: Windows kernel driver vulnerability (CVE-2025-24990), actively exploited in the wild

That’s three generations of programmers on both Windows and Linux all making the same mistake. The glibc syslog bug from 2024 is almost identical to one reported in 1997, and 25 years later someone made the exact same mistake in newer code.

Memory-safe languages exist, but most critical infrastructure still runs on C and will for decades.

52 years later and we’re still finding the same bugs in different code. History doesn’t repeat, but it definitely rhymes.

The complete Unix v4 source code is now in the Unix History Repository on GitHub.

Hacking is not a hobby but a way of life. 🎯

This article is based on multiple sources including coverage from The Register, the oss-security mailing list, Hacker News, the Metzdowd cryptography mailing list, and Richard Weinberger’s technical analysis.

→ Stay updated!

Get the latest posts in your inbox every week. Ethical hacking, security news, tutorials, and everything that catches my attention. If that sounds useful, drop your email below.